Parts of the remains of a Russian ground complex in Russekeila. The site is large and belonged to Russian overwintering hunters in Svalbard during the first half of the 19th century. (Image: Kolbein Dahle/The Governor of Svalbard)

Parts of the remains of a Russian ground complex in Russekeila. The site is large and belonged to Russian overwintering hunters in Svalbard during the first half of the 19th century. (Image: Kolbein Dahle/The Governor of Svalbard)

Hunting station Fredheim in Sassendalen. (Image: Sissel Aarvik / The Governor of Svalbard)

Hunting station Fredheim in Sassendalen. (Image: Sissel Aarvik / The Governor of Svalbard)

Hunting station Fredheim after the relocation in 2015.

Hunting station Fredheim after the relocation in 2015.

Gammelhytta in Fredheim. It was also commonly called Danielbua. (Image: Sissel Aarvik / The Governor of Svalbard)

Gammelhytta in Fredheim. It was also commonly called Danielbua. (Image: Sissel Aarvik / The Governor of Svalbard)

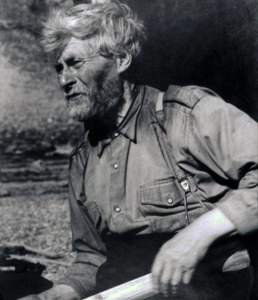

“I will always remember the freedom of the great plateaux”.– Hilmar Nøis. (Image: The Museum of Svalbard)

“I will always remember the freedom of the great plateaux”.– Hilmar Nøis. (Image: The Museum of Svalbard)

The crucifix on the unfortunate crew’s grave. They intended to overwinter between 1872 and 1873. There was originally an inscription on the crucifix, which is believed to have read “Here rests the dust of 15 men, who died here in Mitterhuk in the year 1873. Peace for their dust”. Today this inscription is illegible. (Image: Asbjørn Børseth / The Governor of Svalbard)

The crucifix on the unfortunate crew’s grave. They intended to overwinter between 1872 and 1873. There was originally an inscription on the crucifix, which is believed to have read “Here rests the dust of 15 men, who died here in Mitterhuk in the year 1873. Peace for their dust”. Today this inscription is illegible. (Image: Asbjørn Børseth / The Governor of Svalbard)

Svenskhuset on Kapp Thorsen with the new crucifix from 2013. The inscription reads “Here rests the dust of 15 men, who died here in Mitterhuk in the year 1873. Peace for their dust”. (Image: Snorre Haukalid / Governor of Svalbard)

Svenskhuset on Kapp Thorsen with the new crucifix from 2013. The inscription reads “Here rests the dust of 15 men, who died here in Mitterhuk in the year 1873. Peace for their dust”. (Image: Snorre Haukalid / Governor of Svalbard)

The Governor of Svalbard is in charge of repairs needed to keep Svenskehuset as well preserved as it is today. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

The Governor of Svalbard is in charge of repairs needed to keep Svenskehuset as well preserved as it is today. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

A tractor that has seen better days is parked on the beach in Gipsvika. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

A tractor that has seen better days is parked on the beach in Gipsvika. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

Isfjorden was observed by Willem Barentsz as early as 1596. He describes the inlet to the fjord system as “Grooter Inwijck”. In 1607 Hudson referred to Isfjorden as “The Great Indraught”. These are both descriptions of the mouth of the fjord, not names for the fjord system. It was Poole who, in 1610, first named the fjord “Ice-Fjord” – the name that has been kept.

The oldest traces of human activities that can be found along the beaches of Isfjorden are remains of whaling dating from the 1600s and 1700s. Whalers built their stations by the outlet of Isfjorden, where bowhead whales appeared in the summer. In Trygghamna, by the outlet of Isfjorden, remains of early western European whaling can be found on the beach in the form of tryworks – facilities for rendering blubber into oil. Other remains of what must once have been a large whaling station have been obliterated. The inner arms of the fjord, such as Dicksonfjorden and Ekmanfjorden, do not appear to have been attractive to the early whalers: they kept to the outer areas of the fjord.

After the whalers left Isfjorden, Pomors (Russians from the area of the White Sea) took over the fjord area. The Pomors concentrated on hunting walrus and furred animals as well as gathering down. They also hunted reindeers, seals and birds and collected eggs. Remains of large and small hunting stations can be found along Isfjorden. Many of these stations were in use all year round since the coats of foxes and polar bears were valuable and provided a strong motivation for overwintering. Evidence of the fact that the Pomors stayed for many years can be witnessed in several places around Isfjorden.

Russekeila is a bay to the south of the fjord, between Festningen and Kapp Linné. This is where the Russians stayed for many years. Today, traces of 18th and 19th century hunting activities are visible in the form of extensive remains of Russian settlements. One of Svalbard’s largest historical sites, Russekeila also consists of foundations for Russian crosses and graves. The area offered good mooring conditions and was well suited for hunting. Today, it is the best place in Svalbard for catching Arctic char.

In Isfjorden there is also evidence of Norwegian overwintering hunting dating from the 1800s and 1900s. It was often similar to Russian hunting, involving the same products. The hunters set up cabins and field stations all over the Isfjord area. Only a few of these are still there today. At Fredheim, in Sassenfjorden, hunter Hilmar Nøis’s station can still be found. This also served as his home for many years. He spent 38 winters in Svalbard, though Fredheim was not his base through all of these. In Fredheim there are two generations of hunters’ cabins. The building of the main one, which Hilmar Nøis called “Villa Fredheim”, was commenced in 1924. It has since been converted and enlarged several times. Fredheim is one of the largest hunting stations in Svalbard, and it has been used as the main station since the middle of the 1920s. A lot of credit for Fredheim should be given to Hilmar's second wife, Helfrid Nøis. She contributed to making Fredheim more homely, introducing a flagpole, green plants, curtains and tablecloths. This made Fredheim very different from the typical hunter’s cabin. But it was also a workplace: a hunting station with outlying field stations and outdoor trap guns for polar bears and foxes.

To the east of Villa Fredheim is the cabin Gammelhytta, also called Danielbua. It was used by Daniel Nøis during his stay in the winter between 1911 and 1912, but is believed to be built around 1900–1903 by Lars Nisja. The land around Fredheim tends to erode and in 2001 Gammelhytta had to be moved so it would not slide into the sea. The hut was then restored in the same year. Today it looks just as it used to, with moss to seal the gaps between the beams in the walls, and bark and turf covering the exterior and the roof. Due to persistent erosion, Villa Fredheim and the two other buildings were relocated further from the sea in 2015.

Hilmar Nøis often goes by the name of “The King of Sassen”. He was born in Risøyhamn in Andøya, continental Norway, in 1891 and died in 1975. He spent his first winter in Svalbard when he was 18 years old. The last winter he spent in Fredheim was in 1963, together with his wife Helfrid.

Hilmar made a living of his hunting. He was captivated by the freedom, the scenery, the vegetation and the animals in Svalbard. There he found he was his own master. But life as a hunter was not always easy; the work was monotonous and he often had to work in extreme cold.

Kapp Wijk is another hunting station that is still in use. There are many field stations in its surrounding area, which show how the hunter utilizes space. There are long traditions here, with three generations of hunting cabins. The legendary hunter Arthur Oxaas is said to have used two of these. The third one was built by Harald Solheim, a hunter who is equally legendary and who still practices today. The place illustrates a development from the most basic lodgings to more comfortable accommodations.

Along the fjord evidence of scientific expeditions can also be found. At Kapp Thordsen Svenskehuset was established by Adolf E. Nordenskiöld in 1872. His goal was to exploit the minerals found in Spitsbergen and to promote scientific work in the polar regions. The idea of Svenskehuset was to begin the commercial extraction of coprolites. This was never realized. The house is known as the location for one of the most famous and tragic overwintering stories in Svalbard. Seventeen Norwegian seal hunters died here the same year the house was built. They had used it for shelter, to escape the brunt of the harsh weather.

Svenskehuset was used as shelter for the winter by a Swedish scientific expedition during the first International Polar Year in 1882-1883. Salomon August Andrée, one of the participants, later died trying to reach the North Pole in a hot air balloon. The house is the only one of the large houses dating from the 1800s that has been preserved.

Svenskehuset and its surrounds are worth visiting and are greatly valued for the area’s cultural legacy and dramatic history.

Traces of several attempts at mining and mineral extraction can be found in Isfjorden, dating from the beginning of the 20th century and onwards. These can be found in Skansbukta and Gipsvika, for example. The latter is located to the west of the grand mountain, Templet. Layers of gypsum are easily visible in the flat-topped mountains in the area, giving the place its name. Traces of activity once carried out here by the Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate can still be found, like silent witnesses scattered across the landscape. The Scottish mining company prospected for coal in the early 1900s. They did find it, but they did not succeed in the operations. A cabin built by the company in 1921 stands on the beach. Next to it are a rusty tractor and a few tractor carriages. Like a ray of light, an old road leads to the camp in the valley where the search for coal was carried out. There are also remains of a Russian hunting station in the area, dating from long before the Scots arrived there. The station is from the 1700s, when the Pomors regularly overwintered in Svalbard while they hunted.

The first permanent year-round residents came to Isfjorden as Norwegian and Russian mining developed in the 1900s. They settled in Longyearbyen, Pyramiden and Barentsburg. So much coal was found in these places that it became a foundation for a society of a more stationary kind. Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani’s operations in Longyearbyen, and that of the Russians in Barentsburg, created the most stable workplaces in Svalbard. These are the only two mining enterprises that have been running right up to the present. Pyramiden was closed down in 1998.